The Hardest Working River in the West

The Colorado River begins high in the Rocky Mountains of northern Colorado as an icy stream fed by melting snow. From there the river meanders west, through columbine-filled alpine meadows, past Colorado’s Palisade peach orchards, and into the striking red rock canyons of southern Utah. Mule deer, mountain lions, bighorn sheep, bald eagles, and other wildlife flock to this oasis in the desert. The river is brought to a standstill at the border of Utah and Arizona by the Glen Canyon Dam, a towering cement wall that traps the river in the canyon to create Lake Powell. Water released from Lake Powell rushes through the Grand Canyon, delighting boaters and providing refuge to fish found only in the Colorado River Basin. The river is interrupted again by the colossal Hoover Dam to create Lake Mead—the largest reservoir in the nation. Water from Lake Mead flows south along the western border of Arizona before entering Mexico. By this point, the once mighty river is reduced to a trickle before it can reach the Gulf of California.

The Colorado River has helped sustain the lives of millions of Indigenous people throughout the basin since time immemorial. From the aboriginal lands of the Ute Indians to the Pascua Yaqui and Tohono O’odham nations, the water within the river provided life to the land and the communities that thrived in harmony with it. The lifeways created from these communities was in partnership with the land and waters and an inherent part of Indigenous peoples’ individual and collective identities. Today, Tribal nations continue to protect and steward water from the Colorado River for spiritual, cultural, and ecological purposes and to support their economies and communities.

As Western expansion continued, the river brought life to new communities that were established within the basin. The Colorado River now provides water to roughly 35 million people in seven states, 30 sovereign Tribal nations, and Mexico. Its waters sustain critical wildlife habitat, support 16 million jobs, irrigate 5.5 million acres of land, and fuel world-class recreation. However, growing water demands and climate change threaten the Colorado River and our collective ways of life in the West. Equitable, sustainable, and proactive management of the river has never been more important.

A River in Crisis

For more than a century, people have fought over the Colorado River in boardrooms far removed from its riverbanks. Many have come to treat the river as a mere plumbing system and have forgotten that the Colorado River is a wild and dynamic ribbon of life.

When the Colorado River’s water was divvied up a century ago, little or no attention was paid to the needs of the environment. Today, dams, reservoirs, and pipelines have drastically altered the river’s flows and critical wildlife habitat. At the same time, climate change is tightening its grip on the Colorado River. According to scientists, 2000-2021 was the driest 22-year period in the last 1,200 years in the West. During this time, climate change contributed to the loss of 32.5 million acre-feet of water from the Colorado River Basin— roughly enough to fill Lake Mead. While the wet winter in 2023 offered a temporary reprieve, conditions in the West are only expected to get hotter and drier over the long-term. Much of the snow and rain that used to make it into the Colorado River simply doesn’t anymore.

Annual demand for water from the Colorado River exceeds what the river can provide by roughly 1.5 million acre-feet. That is more than double the annual residential water use for the entire Colorado River Basin, or enough water to meet the needs of approximately 15 million people. If we continue on our current path, we could face a water shortage of closer to 3.8 million acre-feet by 2060.

We are demanding too much of the river and causing cascading effects on communities, fish, and wildlife.

What is an acre-foot?

An acre-foot of water is equal to 325,851 gallons, or enough to flood a football field with one foot of water. A single acre-foot of water could meet the needs of two to four families for an entire year.

The white bathtub rings around Lake Powell and Lake Mead serves as an ominous reminder of how much water has been lost from the reservoirs that millions of people depend on. Plummeting water levels threaten water supplies and the ability of the dams to produce hydropower that keeps the lights on in communities across the Basin. This in turn reduces hydropower revenues, which are an important funding source for government programs to protect fish and wildlife.

When reservoir levels drop even lower and reach dead pool, water cannot enter the concrete tubes designed to move water past the dams and downstream. The reservoirs were approaching dead pool in 2022, which would have had catastrophic impacts on the environment and communities.

For a century, the Colorado River has been managed like a simple system of pipes and buckets designed only to deliver water from one city, farm, or powerplant to another. In reality, the river is a dynamic and wild system that is rapidly losing water as the climate gets hotter and drier.

What does “power pool” and “dead pool” mean?

You may hear water managers talk about how close Lake Powell and Lake Mead are to approaching “minimum power pool” and “dead pool” levels. Minimum power pool refers to the minimum water level needed for water to reach dam intakes to generate hydropower. Dead pool is the point at which water levels drop so low that water doesn’t even reach the outlets at the base of the dam that are designed to move water downstream. If Lake Powell were to reach dead pool, water would no longer flow past the Glen Canyon Dam and into the Grand Canyon.

Changes in river flows threaten rare species like the Colorado Pikeminnow (Ptychocheilus lucius), which is only found in the Colorado River Basin. Despite being called a “minnow,” this toothless fish can grow to be 6 feet long and live up to 40 years. The pikeminnow can travel hundreds of miles to spawn and depends on natural fluctuations in river flows to create and maintain its habitat. The pikeminnow was once found throughout the Colorado River Basin, but dams and diversions have since decimated its populations. Matters were made even worse by the introduction of nonnative sport fish, which compete with and prey on the pikeminnow.

Today, the pikeminnow’s range is limited to Colorado, Utah, and New Mexico. It has not been found in the Grand Canyon, or anywhere in the Lower Colorado River Basin, since the 1970s. WRA has been diligently working with state agencies, the federal government, Tribes, water users, and hydropower interests to restore and maintain river flows for the pikeminnow and other rare species.

The crisis on the Colorado River has far reaching impacts on people, fish, and wildlife. We need to stop treating the Colorado River like a pipeline and start treating it like a river.

The Law of the River

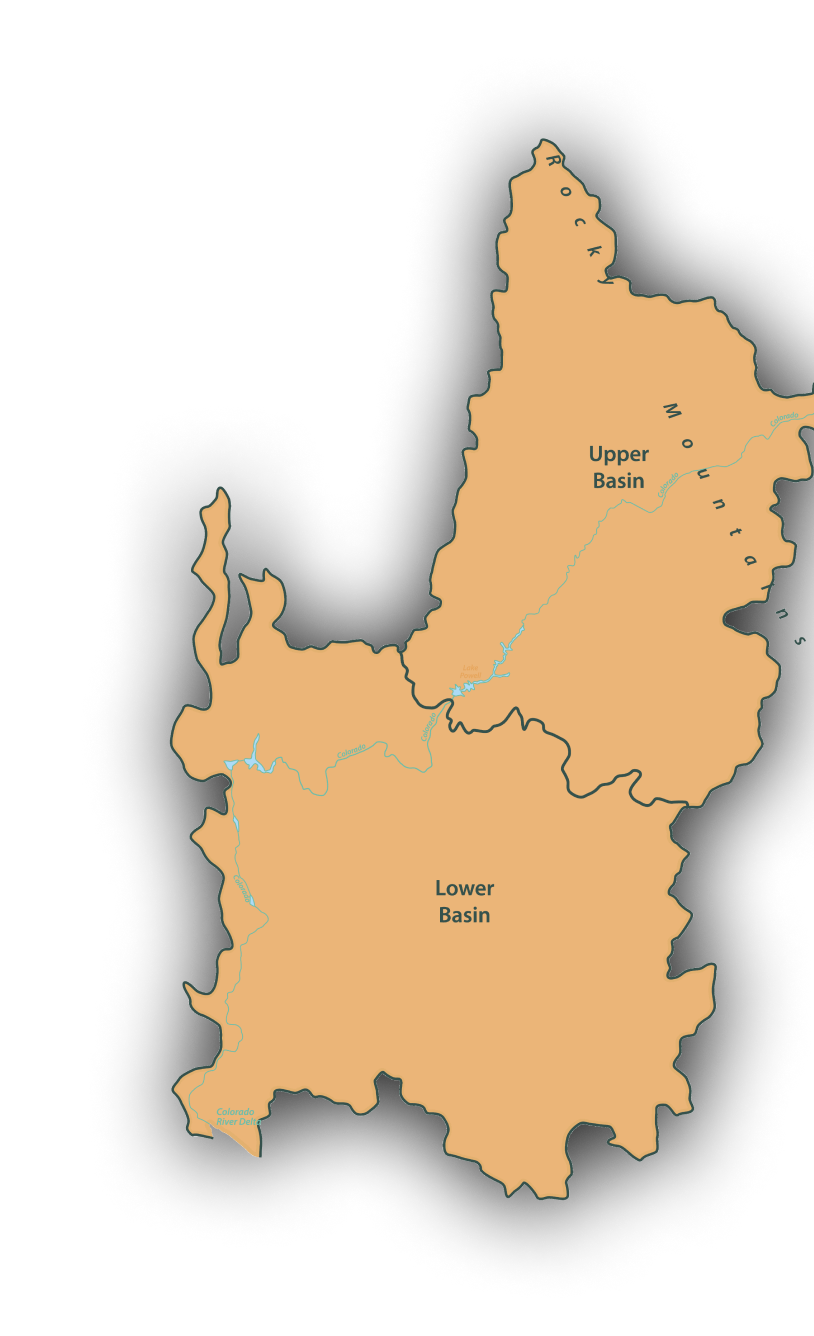

This crisis has been 100 years in the making. Over the last century, the Colorado River’s water has been divvied up by numerous legal agreements, compacts, court decrees, international decisions, and congressional acts collectively known as “the Law of the River.” The foundation of the Law of the River is the 1922 Colorado River Compact, which divided the seven Western states that rely on the river into two Basins and split water between them.

Subsequent agreements dictated how much water individual states and Mexico were entitled to. Despite various United States Supreme Court rulings recognizing Tribal reserved rights – that is, rights reserved by or for Tribes in treaties and other legal agreements that ceded aboriginal lands and/or created reservations – the 30 Tribal nations who have depended on and stewarded the river since time immemorial were systematically and inequitably excluded from participating in the 1922 compact negotiations and have long been denied their fair share of water from the Colorado River. Nearly a century later, Tribal nations still have to nation-build with outdated and inequal laws that govern the river. Despite these ongoing injustices, individual Tribes and the Ten Tribes Partnership continue to advocate at the state and federal levels to protect the health of the Colorado River and their rights to the river’s resources.

Map of Colorado River Basin Tribal Communities

Tribal Water Rights

Inherent in their sovereignty as their own nations and governing bodies, Tribes hold legal rights to use water from the Colorado River but face numerous legal and political barriers to accessing their fair share.

In 1905, the United States Supreme Court affirmed what Tribal nations knew to be true — that Tribes have a right to water. In 1908, the Supreme Court recognized that the establishment of an Indian reservation carries with it a reservation of enough water to carry out the purposes for which the land was set aside. For many Tribes, the purpose of the creation of a reservation is to establish a permanent homeland. It is important to note that these legal recognitions by the federal government are not a grant of rights, but a confirmation of rights that Tribes held and continue to hold as sovereign nations.

While Tribal water rights pre-date the creation of the federal government, they were only given a brief mention in the 1922 Compact. Because Tribes were excluded, their interests and values were not reflected in the plan that the Compact laid out for governing the river and distributing its water. The Compact included states in the river’s governance structure but failed to include Tribes. This has resulted in Tribes being excluded from other important decisions that followed the 1922 Compact. In addition, the Compact divided the Colorado River Basin into two parts, the Upper and Lower Basin, and distributed water between each. While state boundaries fell neatly within the Upper or the Lower Basin, Tribal boundaries did not. For example, the Navajo Nation is in both the Upper and Lower Basin, which poses additional administrative challenges in securing water.

The 1948 Upper Colorado River Basin Compact and a 1963 Supreme Court decision clarified that Tribal water rights are included in each state’s allocation from the Colorado River. For example, part of Arizona’s allocation (2.8 million acre-feet) is supposed to be used to support Tribal lands in the state. However, the specific volume of water that Tribes are entitled to must be determined through lengthy legal proceedings.

Tribes have been working for decades to have their water rights quantified and recognized. Today, 22 Basin Tribes have recognized rights to use 3.2 million acre-feet of Colorado River water each year and 12 have either partially or wholly unresolved water rights. Even those with resolved water rights have been precluded from using their full share of water from the Colorado River due to a lack of infrastructure, insufficient federal funding, and restrictions on how they can access and use their water. Unused Tribal water is often used by others in the Basin without compensating the Tribes. Many Tribes also face legal barriers in participating in compensated water conservation programs, forcing them to miss out on what would be a win-win situation for Tribes and the Colorado River.

In other words, Tribes must endure arduous legal proceedings to determine how much water they are entitled to. After these proceedings, they face barriers in getting the water where it needs to go. Tribal communities throughout the Basin have been left without access to clean running water as a result. For example, on the Navajo Nation, an estimated 30-40% of households are not connected to a public water system and must haul water for their families at an enormous cost.

Tribes have been stewards of the Colorado River since time immemorial and hold some of the oldest water rights on the river, yet they have been excluded from Colorado River negotiations and programs. That needs to change. Tribes must be included in decision-making, receive support in accessing their fair share of water, and be given opportunities to participate in water conservation programs.

Coping with shortages

The Colorado River has been over allocated ever since the ink dried on the first agreement dividing up its water. The compact and other early agreements were based on an unusually wet period in Colorado River history and ignored available data on how much water was actually in the river. We are still dealing with the fallout from this miscalculation more than a century later as water users try to claim all the water that was promised to them on paper— water that, in reality, doesn’t exist.

Agreements made in the early 20th century over promised water from the Colorado River on paper, but there was still enough water to meet actual demands in the Basin. But by the turn of the 21st century, the flawed policy foundation governing the river started crumbling under the weight of climate change, drought, and growing water demands. Existing agreements had doled out the river’s water for decades, but there was no system for dealing with shortages and the river was being sucked dry.

In 2007, the Bureau of Reclamation released a set of interim guidelines that dictated for the first time how water shortages would be handled. The guidelines coordinated water releases from Lake Powell and Lake Mead to provide more certainty to water users and to avoid conflict between the Upper and Lower Basin. The guidelines laid out a tiered system for curtailing water deliveries to the Lower Basin depending on the water levels in Lake Mead. The lower Lake Mead, the deeper the cuts.

In addition to the interim guidelines, clarifications were also made to the 1944 treaty between the United States and Mexico. These clarifications, known as “Minutes,” outlined how Mexico would face shortages based on water levels in Lake Mead. The agreements also included important measures to restore the Colorado River Delta. The first agreement (Minute 319) was signed in 2012. This agreement was extended and expanded on in Minute 323 in 2017.

Connecting the river to the sea

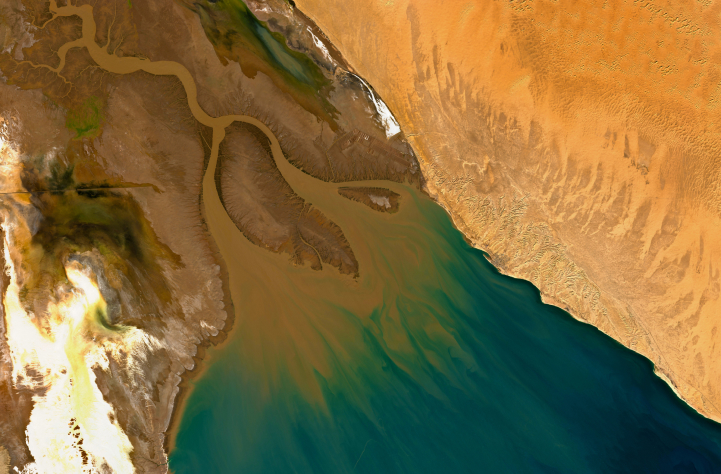

Before dams and diversions, the Colorado River flowed all the way to the Gulf of California. A lush green oasis formed where the river met the sea, providing refuge to birds, bobcats, racoons, coyotes, and other wildlife. But upstream demands for the river’s water have all but dried up this oasis. Minute 319 marked the first time in history that the United States and Mexico agreed to restore river flows in the Colorado River Delta. The first pulse of water was released in 2014. Community members celebrated as water filled the empty riverbed and connected the Colorado River to the sea for the first time in almost 20 years. In 2017, the two nations agreed to continue efforts to restore the parched delta in Minute 323.

The Bureau of Reclamation recognized that the interim guidelines would need to be revised in the future and so they set an expiration date for 2026. But it soon became clear that the river’s crumbling policy foundation would not hold that long. Faced with looming water shortages, the Colorado River Basin scrambled to patch the foundation with short-term agreements and emergency actions. For example, a pilot program was created in 2014 to incentivize water users throughout the Basin to reduce consumption on a voluntary and temporary basis. Drought Contingency Plans were put in place starting in 2019 to outline strategies for dealing with dry conditions in the Basin. In the Upper Basin, these plans set up guidelines for releasing water from upstream reservoirs into Lake Powell. In the Lower Basin, the Drought Contingency Plans established additional cuts depending on water levels in Lake Mead. In 2021, the Bureau of Reclamation began to send water stored in the Upper Basin to Lake Powell to prop up the reservoir. Meanwhile, the Lower Basin worked with Reclamation to create the 500+ plan, which outlined additional conservation strategies to bolster Lake Mead.

Water for fish and wildlife

In 2022, water levels in Lake Powell dropped so dramatically that water needed to be delivered from upstream storage facilities to prop up the reservoir. WRA worked with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to time the release of this water to benefit the environment, resulting in a win-win for fish, anglers, boaters, and downstream users.

That same year, the Jicarilla Apache Nation agreed to lease up to 20,000 acre-feet of water to the New Mexico Interstate Stream Commission to benefit threatened, endangered, and sensitive fish in the Colorado River Basin.

Despite these efforts, water levels in Lake Mead and Lake Powell fell to record lows. In 2021, the Bureau of Reclamation declared the first ever water shortage on the Colorado River.

It became clear that the 2007 Interim Guidelines were no match for the dry conditions on the river. In 2022, the Bureau of Reclamation announced that, as a stop-gap measure, it would work with the Basin to update the guidelines before they expired in 2026. That same year, the federal government called on the Basin states to cut their water use by 15-30% and announced that it would invest in projects to conserve water in the Upper and Lower Basin. In response, the Lower Basin put forth a proposal in 2023 to temporarily curb their water use through 2026. Although the proposal is a start, it is not enough to solve the West’s water crisis.

The Bureau of Reclamation has since kicked off the process of working with the Basin states, Tribes, and stakeholders to draft new guidelines for managing the river after 2026, when the current interim guidelines expire.

Key Moments on the Colorado River

The Future of the River

History has shown that we can’t fix the river’s crumbling foundation with short-term, emergency agreements. Now is our chance to put in place forward-thinking solutions to protect the hardest working river in the West.

The future of the Colorado River depends on our ability to implement equitable and forward-thinking strategies to conserve water and keep the river healthy and flowing.

At WRA, we believe the policy foundation governing the river must include five principles:

Cut water consumption by 25%

Cities, farms, ranches, and businesses throughout the Colorado River Basin must take steps to cut water consumption by at least 25% over the next few years, and we should take large new non-Tribal water development (activities that take more water out of rivers) off the table until a sustainable path has been identified.

Account for current and future conditions

Colorado River policies must reflect the fact that there is less water in the river today, and there will be less water in the river in the future due to a warming, drying climate. These policies must be flexible, proactive, equitable, and sustainable for all states, Tribes, and stakeholders.

Maintain healthy river flows

Healthy river flows must be maintained and restored, and reservoir water releases timed to support irreplaceable ecosystems and recreational uses along the Colorado River and its tributaries.

Include Tribes in Decision-Making and Ensure Water Access

The 30 federally recognized Basin Tribes, many whose water rights, infrastructure needs, and values have long been put on the back burner, must be included in decision-making and have equitable access to clean drinking water.

Include impacted people, parties, and stakeholders

Decision-making forums should be transparent, accessible, meaningfully inclusive, and enable input from a broad range of impacted people, conservation groups, and other important stakeholders.

News

We must use this historic opportunity to protect the Colorado River and all who rely on it. Learn more about these principles and strategies for implementing them.