April 4, 2024

For more than a century, disputes over the Colorado River have unfolded in boardrooms far removed from its wild rapids and red rock canyons. Early agreements treated the river as though it was nothing more than a pipeline and doled out its limited water without regard for the health of the river and without a plan for dealing with water shortages. Today, growing water demands and climate change threaten the Colorado River and our way of life in the West. But it doesn’t have to be this way. The federal government is working with states, Tribes, and stakeholders in the Colorado River Basin to update the guidelines for governing the river.

Now is our chance to adopt policies that treat the river as a dynamic, interconnected, and living system.

How We Got Here

The Colorado River crisis has been building for more than 100 years. Over the last century, the river’s water was divvied up by numerous legal agreements, compacts, court rulings, international decisions, and congressional acts, collectively known as the “Law of the River.” Central to the Law of the River is the 1922 Colorado River Compact, which split the river’s seven-state domain into two basins and divided the water between them. Tribal nations that have stewarded and relied on the river since time immemorial were excluded from these early agreements and have long been denied their fair share of water from the river.

Early agreements promised the states more water than the river could realistically provide, yet there was no system for dealing with water shortages until 2007 – when the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation adopted the Interim Guidelines. These guidelines coordinated water releases from the river’s two major reservoirs, Lake Powell and Lake Mead, and outlined a tiered system to manage water distribution to the Lower Basin based on the water levels in Lake Mead. The lower the water levels got in Lake Mead, the deeper the cuts. But the 2007 guidelines were no match for climate change and unsustainable water demands. Reservoir levels plummeted to record lows prompting a series of stop-gap measures to stave off catastrophe.

The 2007 guidelines are set to expire in 2026 and the Bureau of Reclamation is now working with the Colorado River Basin states, Tribes, and stakeholders to develop new guidelines for governing the river. These new guidelines are an opportunity to chart a new course.

Policy Proposals for Governing the Colorado River

In March, the states in the Upper Basin (Colorado, Utah, New Mexico, and Wyoming) and the Lower Basin (Nevada, California, and Arizona) released competing proposals for governing the river after failing to reach a consensus. While these proposals showed that the basin states are willing to do more to address the region’s water challenges than they have in the past, both fail to protect the health of the river and the ecosystems that sustain the West. The good news is that we are not limited to just the Upper and Lower Basin proposals.

There is another path forward to protect the hardest working river in the West.

WRA and six other conservation groups across the Colorado River Basin submitted the Cooperative Conservation Alternative to the Bureau of Reclamation. The alternative is based on decades of experience, extensive environmental and policy expertise, and rigorous modeling and analysis.

The alternative includes three WRA priorities to protect river health by:

- Creating the Conservation Reserve to increase water conservation

- Improving reservoir operations

- Shaping river management to protect the environment

1. Creating a Conservation Reserve

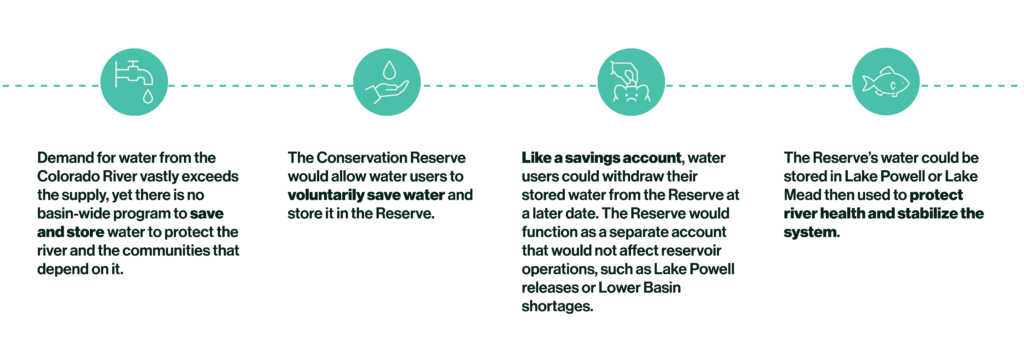

Demand for water from the Colorado River vastly exceeds supply yet there is no basin-wide program to save and store water to protect the river and the communities that rely on it.

The Conservation Reserve expands on an existing program to amplify water conservation efforts. Under the current Intentionally Created Surplus (ICS) program, certain water users in the Lower Basin can reduce their use of water from the Colorado River through measures like improving irrigation efficiency, fallowing lands, or leveraging other water sources. That conserved water is then stored in Lake Mead where it can help stabilize the reservoir. Water users may withdraw their water at a later date depending on system conditions and other factors.

This current program has several shortcomings. For example, ICS water can only be stored in Lake Mead and cannot be used to benefit upstream ecosystems like the Grand Canyon. ICS water is also not kept separate from the water used in routine reservoir operations.

While the ICS program has provided some benefit to Lake Mead, its impact is limited – that’s where the Conservation Reserve comes into play.

The Conservation Reserve creates a water savings account to protect the river and all who rely on it.

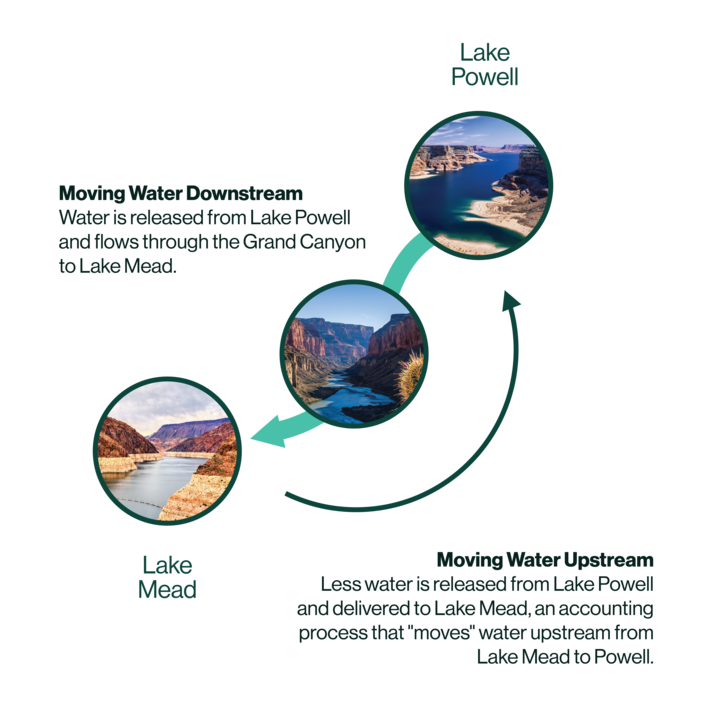

The Conservation Reserve builds on programs like ICS to increase water conservation to benefit communities and the environment. Water users would have the opportunity to conserve some of their water and save it in the Reserve. While in the Reserve, this water could be stored and moved between Lake Powell and Lake Mead to benefit river health.

Unlike the ICS program, the Reserve would operate as a separate savings account that would not affect reservoir operations or Lower Basin shortages. In other words, the Reserve water is set aside to be used for river and ecosystem protection, not for day-to-day activities – much like keeping a separate checking and savings account. Like a savings account, water users who contribute to the Reserve could withdraw their saved water at a later date.

The Reserve’s water would be managed by the Bureau of Reclamation in collaboration with the basin states to protect river health and stabilize the system. For example, the Reserve’s water might be stored in Lake Powell and released through the Grand Canyon to benefit native fish. Once this water reaches Lake Mead, it could be “moved” back upstream using an accounting process and released through the Grand Canyon again. Future iterations of the Reserve could even allow water to be moved farther upstream to benefit streamflow in the Upper Basin.

By allowing the water to be stored and moved within the basin, we can maximize the ecological and community benefits of every drop saved.

2. Improving Reservoir Operations

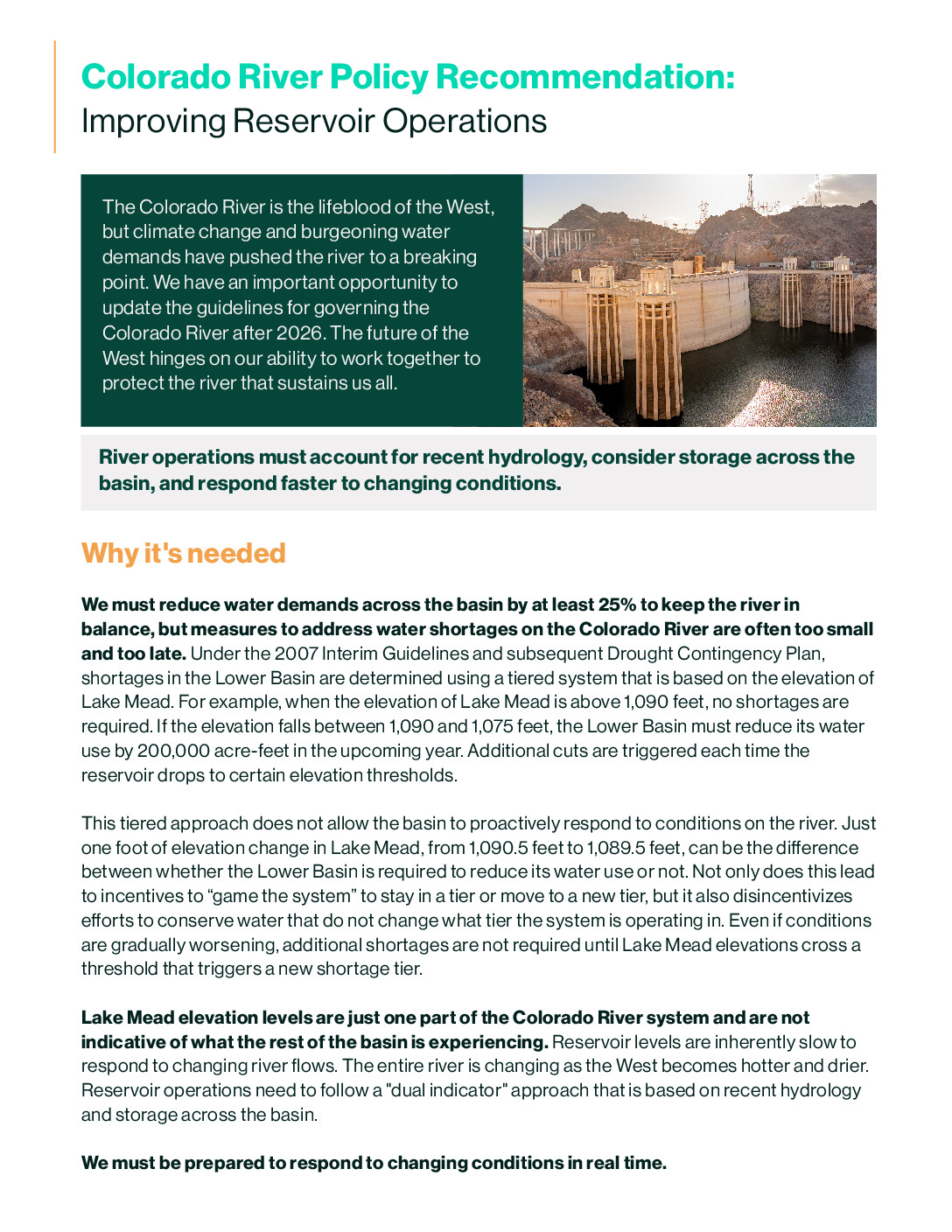

At WRA, we know that we must reduce water demands across the basin by at least 25% to protect the river. But current measures to address water shortages on the Colorado River are often too small and too late.

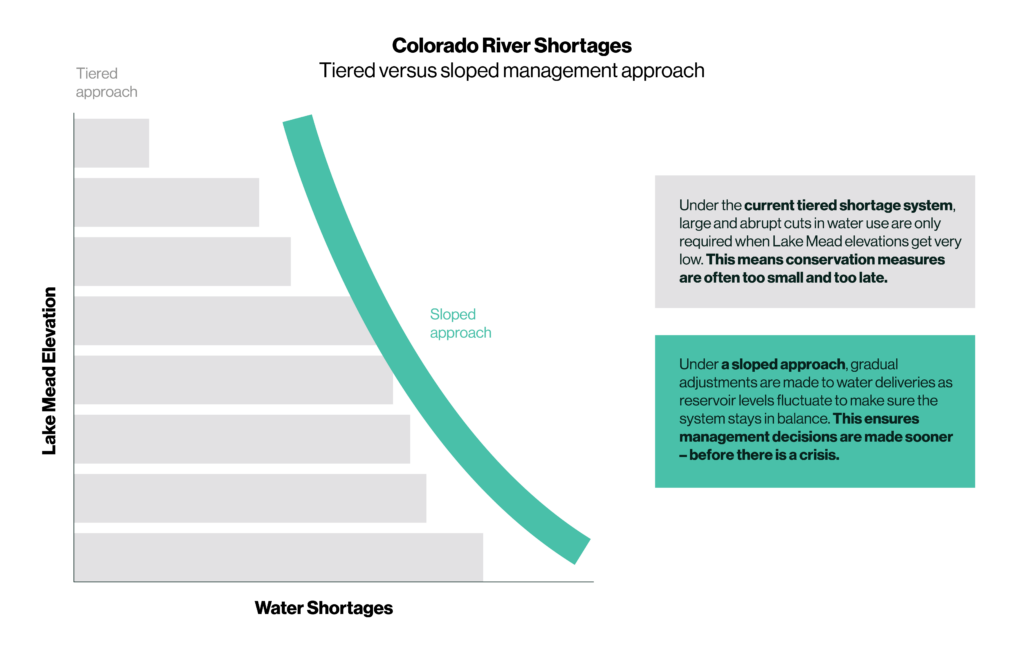

Under previous agreements, shortages in the Lower Basin are determined using a tiered system that is based on the elevation of Lake Mead. For example, when the elevation of Lake Mead is above 1,090 feet, no shortages are required. If the elevation falls between 1,090 and 1,075 feet, the Lower Basin must reduce its water use by 200,000 acre-feet in the upcoming year. Additional cuts are triggered each time the reservoir drops to certain elevation thresholds.

The problem is that this tiered approach does not allow the basin to proactively respond to changing conditions on the river. Even if conditions on the river are gradually worsening, additional shortages are not required until Lake Mead elevations cross the threshold that triggers a new shortage tier.

Lake Mead elevation levels are just one part of the Colorado River system and are not indicative of what the rest of the basin is experiencing. Reservoir levels are inherently slow to respond to changing river flows. And the entire river is changing as the West becomes hotter and drier. Reservoir operations need to be based on recent river flows and reservoir storage across the basin.

We must be prepared to respond to changing conditions in real time.

Future reservoir operations should:

- Account for recent river flows, especially as climate change and aridification impact the basin. For example, declines in river flows must be factored into decision making around river operations.

- Consider combined system storage, not just the water levels in Lake Mead. The basin is a connected system. Many upstream reservoirs also impact the available water supply. The water levels in Lake Mead alone do not tell the full story.

- Respond faster to changing conditions by making gradual adjustments to water deliveries sooner. Waiting for water levels to plummet before we start taking shortages is like waiting for our car to run out of gas before we start looking for a place to refuel. The longer we wait, the fewer options we have. We also need to recognize that there is less water in the river today and there will be less water in the future as climate change tightens its grip on the West. Water users across the basin will need to commit to proactive measures to use less water.

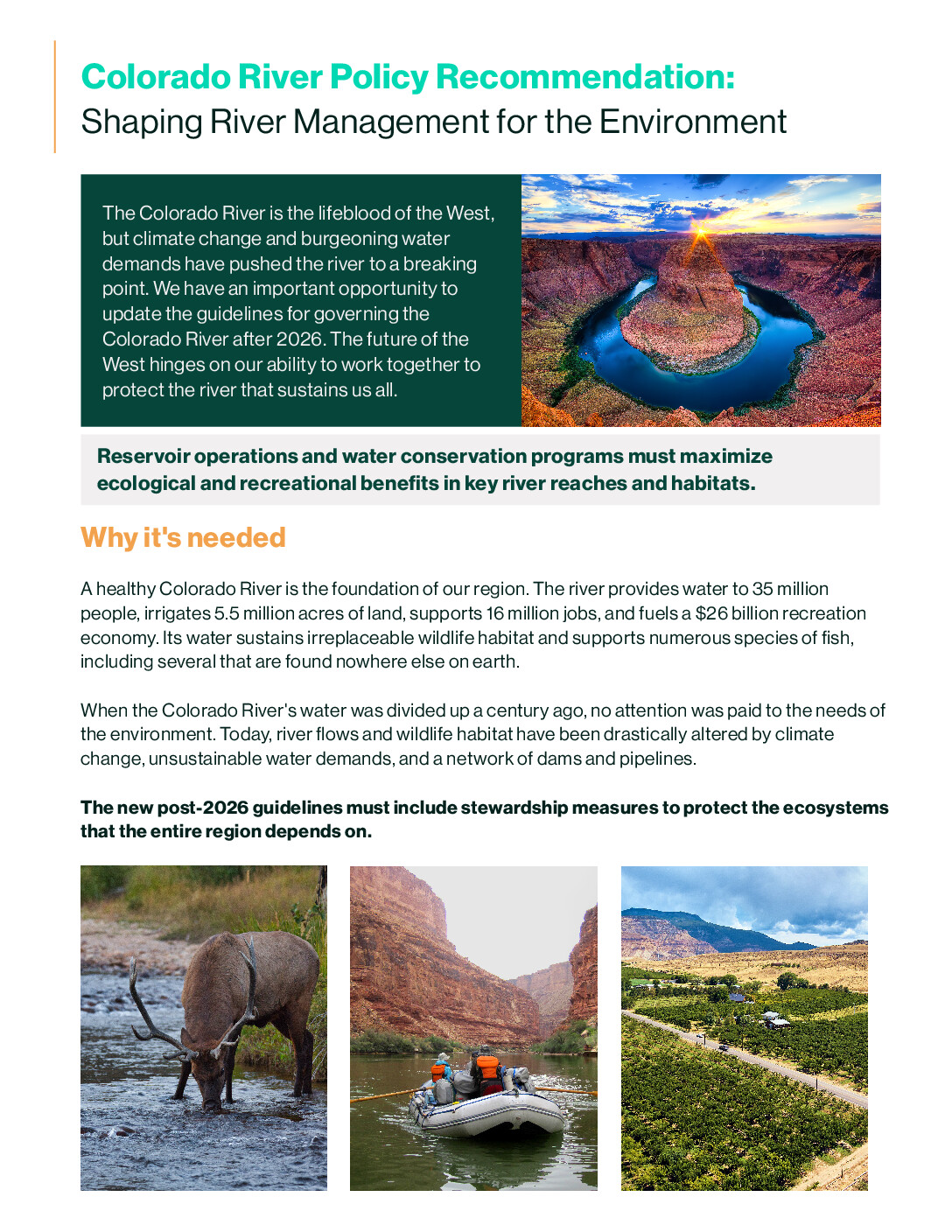

3. Shaping River Management to Protect the Environment

A healthy Colorado River is the foundation of our region. The Colorado River provides water to 35 million people, irrigates 5.5 million acres of land, supports 16 million jobs, and fuels a $26 billion recreation economy. Its water sustains irreplaceable wildlife habitat and supports numerous species of fish, including several that are found nowhere else on earth.

When the Colorado River’s water was divided up a century ago, no attention was paid to the needs of the river itself. Today, river flows and wildlife habitat have been drastically altered by climate change, unsustainable water demands, and a network of dams and pipelines.

The Bureau of Reclamation must consider the environment in its analysis to develop new guidelines for governing the river.

The new guidelines should protect the ecosystems that the entire region depends on by:

- Managing reservoir releases to benefit river health and recreation, including meeting recommended flows for endangered fish and wildlife and peak seasons for recreational boating. This is especially true when operations are changed to address drought or unanticipated circumstances. For example, in 2022, water levels in Lake Powell fell so dramatically that water needed to be delivered from upstream reservoirs to stabilize the system. WRA worked with the Fish and Wildlife Service to time the release of this water to benefit the environment, resulting in a win-win for fish, anglers, boaters, and downstream users. Future water releases should be similarly coordinated to maximize ecological and recreational benefits.

- Including criteria to prioritize water conservation projects that benefit key river reaches. The basin states and the Bureau of Reclamation should also have authority to move that saved water downstream at times and in volumes that will benefit river health and recreation while still meeting the needs of water users.

The people of the West are bound together by the Colorado River – whether we’re fly fishing in the Rocky Mountains, rafting the Grand Canyon, or turning on the tap in Las Vegas. Our entire region must work together to protect the river we all depend on. The Cooperative Conservation Alternative provides a roadmap for doing just that.