February 3, 2025

In the first installment of this series, we looked at what Integrated Resource Plans (IRP) are, what they’re composed of, and why the IRP process is one of the most significant ways we can influence the energy future of the Interior West. It’s clear that IRP processes are complex and multifaceted. And while IRPs in the Interior West share many similarities, the process in each state is different, often substantially so. The process in every state carries unique challenges that WRA works to address.

Working closely with utilities, regulators, and other stakeholders in each state, WRA operates with a level of technical expertise needed to effectively influence and guide the IRPs of major utilities. In this blog, we’ll examine the resource planning processes in Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah, and give a 100,000-foot view on how each one works — and what aspects need improvement.

The Elements of an Effective IRP

The Elements of an Effective IRP

Across the Interior West, IRPs present an opportunity for utilities to shape our energy future and demonstrate to regulators that families and businesses will have affordable, reliable, and sustainable energy.

For WRA, there are four pillars that define an effective IRP:

Comprehensive

An IRP should accurately model the full suite of costs, system impacts, capabilities, and value of available energy resources. transmission and distribution systems.

Aligned

IRPs should meet planning requirements like affordability, safety, and reliability, as well as state policy directives, like clean energy standards or pollution reduction obligations.

Trusted

The IRP process works best when it is transparent, well-vetted, and includes robust and diverse stakeholder input and a fair, competitive process for project developers and technologies.

Impactful

An IRP should be subject to commission review and approval. The utility’s subsequent resource-related decisions should be consistent with the prior, commission-approved IRP.

State by State Processes

Jump to: Arizona | Colorado | New Mexico | Utah

Arizona

Arizona’s investor-owned utilities file IRPs every three years. These IRPs include 15-year forecasts of energy demand and resources to meet predicted load, including a three-year action plan.

The IRP process in Arizona is dramatically less robust than other states. Here, plans are acknowledged, not approved, by the Arizona Corporation Commission, whose five commissioners are elected rather than appointed. The acknowledgement process is of limited impact: IRPs are disconnected from resource acquisition decisions of utilities and do not bind their future actions.

Historically, the Commission tends to acknowledge IRPs. However, in 2018, the Commission declined to acknowledge the IRPs submitted by the state’s investor-owned utilities, which was a positive move to protect Arizona communities. The agency ordered the utilities to develop plans that reduced their dependence upon methane gas and new, gas-fired power plants. The Commission also issued a temporary pause on the construction of new gas plants with a generating capacity of more than 150 megawatts until the end of 2018.

Through formal testimony and comment letters filed with the Commission in proceedings in 2023, WRA recommended several improvements to Arizona’s IRP process. These include staggering the years in which IRPs occur for different utilities. Unlike New Mexico and Colorado, Arizona requires that IRPs for all of the state’s electric utilities are filed at the same time. This means that the Commission’s staff receives more than 500 pages of data all at once from each major electric utility, like Arizona Public Service and Tucson Electric Power, and have minimal resources and capacity for thoroughly evaluating the IRPs.

Requiring the same deadline for all Arizona regulated utilities unnecessarily complicates an already complex process by combining multiple utilities into a single proceeding, with filings located in one case, or docket. For example, customers are dissuaded from engaging in the IRP process because they are uncertain about how to participate when multiple utilities are combined into one hearing. Evaluating each utility’s IRP within its own separate case would provide clarity for customers and a more meaningful opportunity to participate.

Additionally, there is a long-term need for the IRP process in Arizona to be more directly linked to the new resources utilities acquire. This would ensure IRPs are an effective tool for evaluating which mix of supply-side and demand-side resources will reliably meet energy demand while keeping costs low and mitigating risks from natural disasters and other potential disruptions to the grid.

Colorado

Of the states in which WRA works before public utility commissions, Colorado has the most robust resource planning process. Colorado’s process is known as electric resource planning, or ERP. Where other states combine multiple parts of the IRP process into one, Colorado utilities are required to file their IRP in two phases. The Colorado Commission also separately reviews other types of plans that are later incorporated as subcomponents of IRPs. For example, Xcel Energy, the state’s largest electricity provider, breaks out its demand-side management and beneficial electrification plans separately.

Utilities regulated by the Colorado Public Utilities Commission, like Xcel and Tri-State Generation and Transmission Association, are required to submit ERPs every four years. Unlike Arizona, required utility ERP filings are staggered so the Commission typically reviews only one filing per year. Utilities do have the opportunity to file interim ERPs if they desire.

Colorado uses a two-phase ERP process that provides more rigorous Commission oversight and transparency than in states like Nevada.

Phase One

In the first phase of an ERP, utilities present the various components of the plan for Commission review and approval. This includes what modeling assumptions the utility will use to evaluate bids, documents the utility will use to solicit bids, projected load growth and resource needs, and impacts of any retiring generation, like coal plants (Colorado’s 10 remaining coal units will be phased out by 2031.) The utility also presents illustrative resource portfolios constructed to meet system demands using generic assumptions about the costs of different resources.

Phase One is fully litigated, meaning the Public Utilities Commission functions like a courtroom — it follows a formal procedure with filings, testimony by sworn witnesses, and cross examination. This allows for transparency into the modeling for the Public Utilities Commission and intervenors, promotes public accessibility, and ultimately yields better planning.

In Phase One, the Commission provides direction to utilities about their approach to load forecasts, including the requirements for assumptions and methodologies that the utility must use to determine the expected load growth.

After the Commission issues its decision on Phase One of the ERP, the utility taps the market to solicit bids for generation resources that will meet the approved resource need. This marks the beginning of Phase Two.

Phase Two

Colorado’s utilities tend to conduct all-source competitive request for proposal, soliciting bids from all potential suppliers, regardless of their technology or resource type. All-source solicitation allows utilities to make strong decisions informed by the market, without favoring any particular technology. This is important because technology, costs, and market dynamics are always changing – what was a safe assumption five years ago is likely to be upended as innovation progresses.

After the utilities receive bids from vendors, they conduct a round of modeling on all the potential portfolios, using the modeling assumptions approved in Phase One. In 2023, Xcel Energy examined 20 different portfolios to look at how different combinations of bids performed, looking at things like cost, longevity, efficiency, and environmental impact. Due to the complexity of resource planning, modeling can be a black box. To mitigate this, Colorado requires an independent evaluator to review modeling work and ensure it’s consistent and fair across all bids. The evaluator provides the Commission a report to review.

Phase Two is not litigated, meaning it’s not a formal legal proceeding but is instead comment-based. This balances the value of public engagement while recognizing need for regulatory efficiency to allow a swift process.

The two-phase structure of Colorado’s process creates transparency and utility accountability, while also harnessing market forces to the benefit of customers. Ultimately, the Commission selects and approves the portfolio and resources that a utility may acquire. This may not be the cheapest choice — unlike some other states, Colorado’s Public Utilities Commission is not constrained to selecting whatever energy mix is least-cost.

Like New Mexico, Colorado plans to achieve net-zero energy production by 2050, and state statutes define specific, economy-wide greenhouse gas emissions reduction targets. In a law approved in 2023, Colorado’s updated economy-wide targets are:

- 65% by 2035

- 75% by 2040

- 90% by 2045

- 100% by 2050

The trajectory for electric utilities is steeper:

- 80% by 2030

Even with its extensive ERP process, there are still challenges in Colorado, particularly around explosive load growth. Xcel projects the need for 5,000 to 14,000 megawatts of resources by 2031. This staggering growth presents considerable challenges in successfully modeling potential bids. Colorado utilities have a resource acquisition period of six years to meet capacity and reliability needs. This may test whether the state’s process can handle such massive load growth in a relatively short window of time.

New Mexico

New Mexico’s three investor-owned utilities are required to file IRPs every three years. The IRPs must include 20-year forecasts of energy demand, and what resources the utility would need to meet that load.

In 2022, the New Mexico Public Regulation Commission modified the state’s rules governing the IRP process. The changes included adding two new requirements for utilities: a statement of need, and a facilitated stakeholder process.

In the statement of need, a utility must define and clearly communicate to stakeholders the types of resources needed to meet a utility’s projected load growth. The statement builds on the Commission’s existing requirement that utilities present a most cost-effective portfolio, or MCEP, in their IRPs. In constructing a MCEP, New Mexico utilities are required to balance three priorities: reliability, affordability, and environmental impacts of resources needed to meet projected load growth. These requirements are similar to those in other states.

Another primary component of an IRP in New Mexico is a utility’s action plan. Ideally, the action plan is influenced by feedback collected during the facilitated stakeholder process. In its 2023 IRP, PNM outlined a nine-part action plan, which included issuing an all-source RFP for resources that would come online between 2029 and 2032.

After the conclusion of the stakeholder process, the utility files its IRP with the Commission. Once the IRP is filed, stakeholders can submit additional comments. Following this comment period, the three-member Commission ultimately decides whether to accept the statement of need and the action plan of the IRP, or to send the IRP back to the utility for refiling if they find it lacking in some way. For example, the Commission could ask that a utility model a portfolio of all emissions-free resources or one that is technology-neutral.

In 2019, New Mexico passed the Energy Transition Act. This landmark law was created to help the state transition away from coal and toward clean energy resources. Like statues in Colorado, New Mexico’s Energy Transition Act requires the state’s utilities to have 40% of their resources be carbon-free by 2025, 50% by 2030, 80% by 2040, and 100% by 2045. PNM says it is on track to achieve 75% carbon-free generation in 2026, and has pledged to produce 100% carbon-free electricity by 2040.

Following the acceptance of an IRP, utilities pivot to issuing requests for proposals for new resources. These requests must be consistent with the portfolio in the final IRP accepted by the Commission.

New Mexico’s lengthy stakeholder process is more inclusive than that found in other states and creates many opportunities for public participation. However, even when accompanied by multiple stakeholder meetings, IRPs involve a high degree of technical analysis, making it hard for most members of the general public to understand and how they can effectively weigh in on the process.

Utah

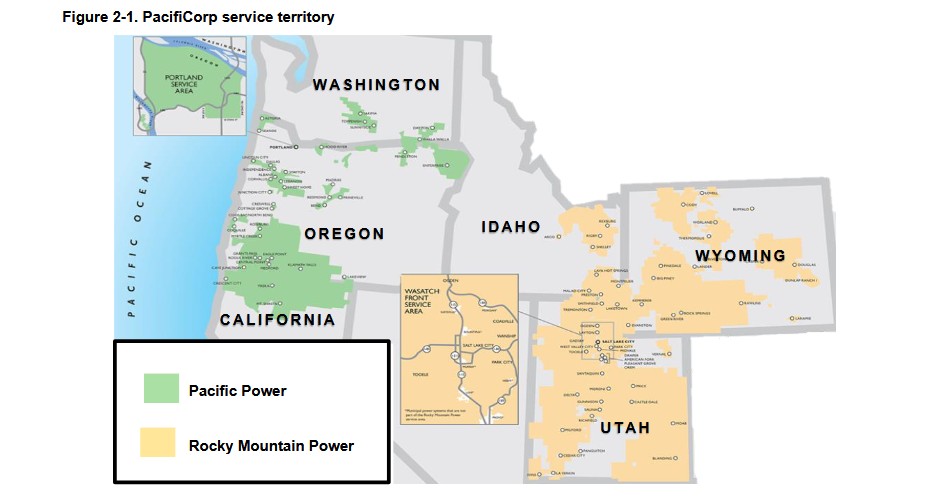

WRA’s work with IRPs in Utah is specific to one utility, PacifiCorp. The utility services customers in six states: California, Idaho, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming. PacifiCorp, which formed in 1999 out of the merger of Pacific Power and Light and Utah Power and Light, is under the jurisdiction of regulatory commissions in six states and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. The company has the largest transmission system in the West. Many of PacifiCorp’s fossil fuel-powered resources are located in Utah, even though each facility may provide electricity in several states.

PacifiCorp prepares its IRPs every two years, filing its plan with state utility commissions during each odd numbered year. For five of its six state jurisdictions, the company receives a formal acknowledgement on whether the IRP meets the commissions’ IRP standards and guidelines.

For even-numbered years, PacifiCorp updates its preferred resource portfolio and action plan by considering the most recent resource cost, load forecast, and regulatory and market information. It also conducts public input sessions throughout its service region.

Key elements of PacifiCorp’s IRPs include:

- A finding of resource need, focusing on the first 10 years of a 20-year planning period.

- The preferred portfolio of supply-side and demand-side resources to meet this need.

- An action plan that identifies the steps the company will take during the next two to four years to implement the plan.

PacifiCorp operates a single system for the benefit of customers in all six states. This is an increasingly complicated balancing act, as the utility’s coastal states have laws that prohibit the use of energy from coal-powered resources. Other states — particularly Utah and Wyoming — want to keep coal units online.

Historically, Utah’s Public Service Commission has prioritized the least-cost/least-risk portfolios over any specific resource type, but due to new state legislation passed in 2024, the agency’s ability to continue this approach remains unclear. PacifiCorp also prioritizes least-cost/least-risk portfolios, and these tend to win acknowledgement from the Commission.

In past IRPs, PacifiCorp would produce a single, least-cost/least-risk portfolio that made it easy to assign specific costs to states that wanted to deviate from that portfolio. In upcoming IRPs, PacifiCorp may present multiple portfolios based on what aligns best to the policies of each state — which will make it more difficult to determine what the overarching least-cost/least-risk portfolio is.

How does PacifiCorp balance pressures from all six states? This is done through a multistate process (MSP) where policies that create specific costs in an IRP are assigned to the states causing them. So, if Wyoming or Utah insist that PacifiCorp must rely on coal resources — whether or not these resources conform with a least-cost/least-risk portfolio — the company will pass those costs on to Wyoming or Utah.

Renewable resources are often included in PacifiCorp least-cost/least-risk portfolios as they help to moderate energy prices, and they’re not subject to the same fuel cost volatility as methane gas plants.

If any one state commission refuses to approve the IRP, PacifiCorp can adjust elements of its IRP during the update phase. For example, in March 2024, the Oregon Public Utility Commission acknowledged only part of PacifiCorp’s 2023 IRP.

Following an IRP, the utility will typically issue an RFP for resources to fill the identified need within a range of specific years. While the IRP identifies specific types of alternative resources to fill future resource needs, RFPs generally seek bids from all resource types. PacifiCorp uses the same modeling tool to select its shortlist of top suppliers as it does to determine its preferred portfolio.

PacifiCorp can issue RFPs at any time, but it needs to show a need for new resources. This does not always need to be done through the IRP process.

The impacts of climate change are also playing an increasingly significant role in PacifiCorp’s planning process. In September 2023, PacifiCorp suspended its 2022 all-source request for proposals due to costs associated with wildfire risk. As legal costs have continued to mount, PacifiCorp most recently estimated $2.4 billion in probable wildfire losses.

States Play a Powerful Role in Crafting Effective IRPs

With the future of many federal programs now uncertain – such as continued incentives from the Inflation Reduction Act – the role that states can play in the transition to clean energy is more important than ever. IRPs are a powerful tool toward meeting the goal of a net-zero future, but only if state agencies structure, require and enforce robust, transparent planning from utilities. Each state has its own challenges, but each can take from the best practices outlined in this blog to ensure a bright climate future for everyone in the Interior West.

WRA’s decades-long work before public utilities commissions across the Interior West affords us a unique vantage point on both the benefits and challenges of each state’s IRP process. Nevada’s process, while regulated in good faith by the Public Utilities Commission of Nevada every three years, contains foundational flaws that have resulted in potentially wasted customer dollars, rushed decision making, and an over reliance on polluting resources. It’s time for a change. Read more about the challenges in Nevada and WRA’s proposed solution in the third and final installment of this series.